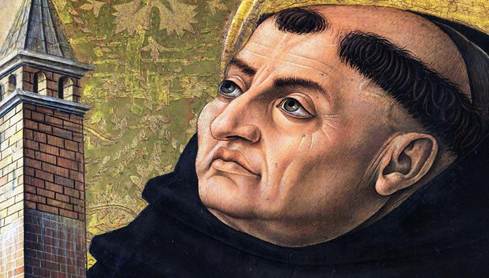

St. Thomas Aquinas

BIOGRAPHY

St. Thomas Aquinas was born into a wealthy family in Rocca Secca, Italy (near Naples) in 1225. Thomas was sent at the age of five to the monastery of Monte Cassino for his education, and then at the university in Naples when he was older. It was at Naples that Thomas was introduced to the philosophers Aristotle, Averroes, and Maimonides, all of whom would come to influence his own theological and philosophical thought, especially Aristotle. At Naples, as well, Thomas heard the preaching of the Dominican father John of St. Julian. He decided to join the new Dominican order, called the Order of Preachers, which upset his family because they had hopes of Thomas entering a much more influential and wealthier Benedictine monastery. His family, in fact, was so determined to keep Thomas from joining the Dominicans that they kidnapped him and imprisoned him in their home for a year, even hiring a prostitute to seduce him away from any thoughts of a celibate life! Thomas ran off the prostitute with a burning log and was so resolved to join the Dominicans that his family finally relented.

Thomas joined the Order of Preachers in 1244. In 1245, Thomas was sent to Paris where he studied under the great Dominican master Albertus Magnus (Albert the Great) and soon became Albert’s favorite student. Thomas was brilliant, but his classmates didn’t think so because his nature was more reserved, so he didn’t say much in class, and they took that to mean he didn’t understand what was going on. His classmates famously nicknamed him “the dumb ox” because of his quietness and his large physique. Albert told these students, “You call him the dumb ox, but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world”.

After four years with Albert in Cologne, Germany, Thomas returned to Paris in 1252. He became admired as a great teacher and theologian. After some time in Rome as a papal advisor, he returned to Paris once more to teach. Finally, he returned to Naples to found a house of studies in 1272. On the way to the Ecumenical Council of Lyons in 1274, Thomas fell ill and died.

St. Thomas Aquinas is known as one of the greatest philosophers and theologians of the Church. He is certainly the greatest theologian between St. Augustine of Hippo and the modern era. His writings include philosophical treatises, theological treatises, and biblical commentary. He also wrote poetry, and he composed hymns that are still sung today. His devotion to the Eucharist was unparalleled. His most famous writings are the Summa theologica (1265-1273, unfinished at his death) and the Summa contra gentiles *1258-1264). St. Thomas was canonized in 1323 by Pope John XXII and declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius V in 1567. He is known as the Angelic Doctor. His feast is January 28.

ST. THOMAS AQUINAS’ ARGUMENT FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD

St. Thomas Aquinas argues that there is a distinction between essence and being. We can know the essence of a man without knowing any particular man, just as we can know the essence of a phoenix, even though phoenixes don’t actually exist. Thomas wrote, “every essence or nature [of a thing] can be understood without knowing anything about its being. I can know, for instance, what a man or a phoenix is and still be ignorant whether it has being in reality” (whether it actually exists). So, the essence of a thing is distinct from its being (its existence in reality).

Also, a thing’s essence cannot be the cause of its being. If it could, then it would be the cause of its own existence, which is absurd. Again, we know the essence of a phoenix, but we see no phoenixes flying about. If a thing’s essence can cause its existence, then we ought to see plenty of phoenixes around. Thomas concludes, “It follows that everything whose being is distinct from its essence must have being from another.”

In light of this, there must be something whose essence is not distinct from its being, whose essence isbeing. And there can only be one something whose essence is being, because if there were more than one there would have to be some kind of difference between them to distinguish one from the other. But how can being be different from being? What could be added to or taken away from being to distinguish it from being? What inherent quality or characteristic of being could there be to distinguish it from being? Posing these questions demonstrates how absurd is the claim that there could be more than one something whose essence is being.

Because nothing can be the cause of its own existence, every thing whose essence is not being is dependent on something whose essence is being. Thomas is thinking here of an essentially ordered series of beings in which the beings exist simultaneously, each causing the next to be. Think of a violinist playing a song. The violinist causes the song to come into being, but the violinist and the song exist simultaneously. Because nothing is the cause of its own existence, then all things whose essence is not being depend on the existence of the previous thing for its own being, and ultimately to the first thing, whose existence is not dependent on any other thing because its essence is being.

Why can’t the series of things that have being go back forever? Because dependent things, by definition, depend on something other than themselves for their being. There cannot be a series of dependent things without a first thing that is not dependent, for then there would be no thing to get the ball rolling. Every thing would depend on the being of … nothing! There would be nothing there to cause the being of the dependent being

Matthew Levering puts it succinctly in his book, Proofs of God: “Fundamentally, Aquinas is arguing that no natural reality that we experience is the cause of its own existence. Nothing that we see around us exists necessarily by reason of the kind of thing it is or the essence or nature it has. This invites us to probe further to find the cause of why things exist until we come to something that exists by its own nature or in which there is no real distinction between nature and existence.”

ST. THOMAS AQUINAS’ ARGUMENT FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD

- We see that there are some things that cause other things.

2. It’s impossible for something to be the cause of itself, for then it would have to exist before it existed, which is absurd.

3. The series of causes can’t go back forever, for then there would be no first cause and, if no first cause, then no dependent causes; so there would be no series of causes at all.

4. It’s necessary, then, to arrive at a first cause, not caused by another, and everyone understands this to be God.

Criticisms of St. Thomas Aquinas’ argument from dependent causes

A common criticism is that Aquinas commits the fallacy of “special pleading” by claiming that God is the uncaused cause, thereby creating an exception to his own rule. The argument states that everything has a cause, but concludes with an uncaused cause. Critics argue that if an uncaused being can exist, there is no logical reason why the universe itself could not be that uncaused entity.

Response: Thomas doesn’t argue that everything has a cause; Thomas argues that everything that has a beginning has a cause. God does not have a beginning (or else He’s not God), so He does not require a cause. This is not special pleading. Special pleading is attributing a characteristic to a member of a group, or applying different standards or rules that you do not attribute or apply to the other members of the group for no justifiable reason.

Presumably, people argue that this is special pleading because God is one member of the group “beings that exist,” and Thomas is attributing to Him characteristics, or applying to Him standards and rules that he is not attributing or applying to other members of this group.

Two things: First, Thomas has a very good reason for treating God differently. He’s God!

Second, God is not a member of the group “beings that exist.” God is existence.

Critics argue that Aquinas’s rejection of an infinite causal chain is not logically required. Assuming a hard stop to the chain is a fallacy, and the argument lacks sufficient justification for why an infinite chain is impossible.

Response: Consider a chain of cars that get in a wreck. The first car breaks down and the second car rams into its back. Then a third car rams into its back. Then a fourth car rams into its back. And on and on. What happens if there’s no first car? Then there’s no chain of cars that get in a wreck. It’s not that the chain of cars starts at the second car instead. No. There’s no chain at all. This is what Thomas is arguing. If there’s no first cause, there are no dependent causes, and no ultimate reaction. There’s simply no chain at all! This is why infinite regression is impossible. What’s interesting is that Thomas didn’t explain why there could be no infinite regression. He just assumed it was obvious to everyone.

Quantum mechanics presents a direct challenge to Aquinas’s premise that everything must have a prior cause. Quantum fluctuations suggest that some events, such as particles “popping into existence,” may occur without a prior, determinable cause. This provides an alternative explanation for the origin of a causal chain, one that bypasses the need for a supernatural first cause.

Response: Dr. David Albert, professor of philosophy at Columbia University and author of Quantum Mechanics and Experience, writes in his New York Times article, “On the Origin of Everything” (March 23, 2013) that:

“Relativistic-quantum-field-theoretical vacuum states – no less than giraffes or refrigerators or the solar system – are particular arrangements of elementary physical stuff. The true relativistic-quantum-field-theoretical equivalent to there not being any physical stuff at all isn’t this or that particular arrangement of the fields – what it is (obviously, and ineluctably, and on the contrary) is the simple absence of the fields! The fact that some arrangements of fields happen to correspond to the existence of particles and some don’t is not a whit more mysterious than the fact that some of the possible arrangements of my fingers happen to correspond to the existence of a fist and some don’t. And the fact that particles can pop in and out of existence, over time, as those fields rearrange themselves, is not a whit more mysterious than the fact that fists can pop in and out of existence, over time, as my fingers rearrange themselves. And none of these poppings – if you look at them aright – amount to anything even remotely in the neighborhood of a creation from nothing.”

Sources: Proofs of God: Classical Arguments from Tertullian to Barth by Matthew Levering, Baker Academic, 2016

Five Proofs for the Existence of God by Edward Feser, Ignatius Press, 2017

https://www.aquinas.edu/offices/campus-ministry/saint-thomas-aquinas.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Aquinas

Be Christ for all. Bring Christ to all. See Christ in all.